Additive manufacturing is a specialized process that constructs parts from the ground up by adding successive layers of material to create a final product. 3D printing is the specific technology most frequently associated with the broader term of additive manufacturing. Conversely, subtractive manufacturing operates by removing material from a larger block to produce a specific part. This latter process traditionally utilizes Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining as its primary method.

Both technologies can leverage computer-aided design (CAD) software models to generate precise physical products. These manufacturing technologies have profoundly transformed the fields of prototyping and production, and they continue to see rapid technological advancements.

This article provides an in-depth discussion of Additive vs. Subtractive Manufacturing, exploring their fundamental differences, associated expenses, diverse applications, and the emerging hybrid manufacturing process.

Additive Manufacturing vs. Subtractive Manufacturing: What are Their Differences?

The distinctions between additive manufacturing and subtractive manufacturing are quite significant. Additive manufacturing, which is often colloquially referred to as 3D printing, functions by adding successive layers of material until an object is fully formed. In contrast, subtractive manufacturing produces an object by systematically removing material from a solid workpiece.

Additive Manufacturing

While both technologies rely on CAD drawings to produce parts, additive manufacturing works by melting or fusing powder, or by curing liquid polymer materials, to build parts based on those digital blueprints. Additive processes are generally slower in terms of manufacturing speed, and several specific technologies necessitate post-manufacturing methods to cure, clean, or refine the surface finish of the product. Often, the surface finish is not as naturally smooth as that achieved through subtractive manufacturing, and the dimensional tolerances are typically not as precise. Nevertheless, these processes are considered ideal for producing lighter parts, optimizing material efficiency, facilitating rapid prototyping, and handling small to medium-batch manufacturing runs.

Complex geometries, such as the direct printing of articulating joints, are uniquely available through additive manufacturing. These geometries can be significantly more complicated than those made via traditional methods, and the setup is usually quick and straightforward, requiring no active operator during the actual printing cycle. The most prevalent materials utilized in additive manufacturing are various plastics and metals. Additionally, the initial equipment cost is frequently lower than that of subtractive manufacturing, and a wide array of material colors is available for most modern 3D printing operations.

The primary additive technologies include:

- Binder Jetting: This process involves liquid bonding agents being selectively deposited to join powder materials together. Common materials include various metals, plastics, ceramics, and sand.

- Directed Energy Deposition (DED): DED utilizes highly focused thermal energy to fuse materials simultaneously as they are being deposited. Materials used in this process typically include wire and powder forms.

- Material Extrusion: In this method, material is selectively dispensed through a nozzle or orifice in successive layers. Compatible materials include plastics, nylons, and specific filaments like FDM and FF.

- Material Jetting: Tiny droplets are selectively deposited to form products. Suitable materials include various photopolymers, waxes, sand, and specialized poly-jetting materials.

- Powder Bed Fusion: Thermal energy is used to selectively fuse specific regions of a powder bed. Materials typically include metals, polymers, and various fibers.

- Sheet Lamination: Individual sheets of material are bonded together to form a solid object. Common materials for this include metal, paper, wood, and plastics.

- Vat Photopolymerization: A pre-deposited liquid photopolymer is selectively cured by light-activated cross-linking of adjoining polymer chains. This process exclusively uses photopolymers.

Subtractive Manufacturing

Subtractive manufacturing involves the systematic removal of material through processes such as turning, milling, drilling, grinding, cutting, and boring. The raw material is typically composed of metals or plastics, and the resulting end product usually features a very smooth finish with exceptionally tight dimensional tolerances. A vast variety of materials can be used in this manner. While change-over times can be longer, the use of automatic tool changers helps to significantly mitigate time-consuming delays. These processes can be fully automated, although a human attendant may be required to oversee the operation of two or more machines simultaneously.

The initial equipment costs for subtractive manufacturing are generally higher and typically require the use of additional jigs, fixtures, and specialized tooling. Consequently, it is best suited for large-scale production runs that benefit from reasonably fast manufacturing times despite the lengthy setup and changeover periods. Material handling equipment is often used to assist both additive and subtractive processes with efficient material loading and removal. However, the geometries achievable through subtractive methods are generally not as complex as those possible with additive manufacturing processes.

Subtractive manufacturing technologies include:

- Abrading: This specific manufacturing process utilizes friction to wear down the material surface, primarily through the grinding and polishing of products.

- CNC Machining Centers: This is a computerized manufacturing process that controls complex machinery via pre-programmed software. It regulates machining equipment to cut and shape parts with high precision. This equipment includes milling machines, lathes for turning, drilling and boring machines, grinders, and advanced 5-axis CNC machining centers.

- Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM): Also known as “spark machining,” “wire burning,” or “wire erosion,” EDM is a non-traditional machining process. It utilizes electrical discharges—ranging in temperature from 8,000ºC to 12,000ºC—to remove material from a workpiece that has been placed in a dielectric liquid.

- Laser Cutting: This manufacturing method utilizes a concentrated gas laser, often CO2, for its energy source. The laser beam is precisely guided by mirrors and directed toward the workpiece to remove material. Typically, the laser beam output ranges between 1,500 and 2,600 watts.

Materials used in subtractive manufacturing processes include hard metals, soft metals, thermoset plastics, acrylic, wood, plastics, foam, composites, glass, and stone.

Comparison Table: Additive Manufacturing vs. Subtractive Manufacturing

|

|

Additive Manufacturing |

Subtractive Manufacturing |

|

Process: |

Builds an object by adding layers of material. |

Creates an object by removing material from a larger workpiece. |

|

Equipment: |

Includes digital manufacturing, 3D printing, and additive fabrication methods such as binder jetting, powder bed fusion, sheet lamination, directed energy deposition, material extrusion, and material jetting. |

Includes traditional machining processes such as CNC machining, laser cutting, EDM, abrading, plasma cutting, and waterjet cutting. Common operations include turning, milling, drilling, grinding, cutting, and boring. |

|

Production: |

Well-suited for prototypes and small-batch production. |

Best suited for mass production. |

|

Equipment Costs: |

Professional desktop printers: $3,500+ |

Hobby-grade mills and lathes: $2,000+ |

|

Accuracy: |

Tolerance as small as 0.004″. |

Tolerance as small as 0.001″. |

|

Area Requirements: |

Desktop printers can operate in most offices or workshops. Industrial printers often require a large footprint on the manufacturing floor and may also require a controlled environment. |

Smaller machines often operate in garages and workshops. Industrial machines typically require a large footprint on the manufacturing floor. |

|

Additional Equipment: |

Some printers require post-processing systems for curing, finishing, and cleaning. Industrial applications may also include material-handling systems. |

May require tooling, fixtures, robotics, and material-handling systems. Coolant systems, tool changers, and waste removal are also often necessary. |

|

Complexity: |

Enables extremely complex designs, including articulating parts. |

Ideal for parts with intermediate geometry. |

|

Cost: |

Typically more expensive than subtractive manufacturing, although plastic prototyping can be much faster. |

Generally less expensive for metal manufacturing. |

|

Materials: |

Primarily plastics. Other materials include metals, ceramics, plasters, graphite, carbon fiber, nitinol, polymers, and paper. |

Materials include hard metals, soft metals, thermoset plastics, acrylic, wood, plastics, foam, composites, glass, and stone. |

|

Properties: |

Thermoset plastics may have potential structural weakness between layers. |

Metals are structurally sound and offer excellent heat resistance. |

|

Set-Up: |

Little to no setup is required. |

Setup is often substantial, though automatic tool changers can help increase machining speed once production begins. |

|

Speed: |

Printing is generally slower than machining, though thermoset printing is typically faster than printing metals. It is often preferred for prototyping and small-batch production. |

A relatively fast process once setup is complete. Best for large production runs due to extensive setup time. |

|

Surface Finish: |

Surface finish can be slightly rough, depending on the material and printing speed. |

Typically produces a smooth finish, with a variety of machining finishes available. |

|

Training: |

Desktop printers are quick to set up, but programming can take time. Industrial printers require training and an attendant. |

Hobby-grade machines require some training. Industrial equipment requires extensive training, and production can be fully automated with attendant oversight. |

Subtractive vs. Additive Manufacturing Cost: Which Is More Expensive?

Additive and subtractive technologies include a wide range of processes, and their costs and capabilities vary from desktop machines to large industrial equipment. In recent years, prices have dropped significantly—especially for additive technologies. Today, compact, easy-to-use desktop additive and subtractive manufacturing tools are available for professional workspaces, machine shops, and workshops.

Entry-level 3D printers start at several hundred dollars, while suitable desktop printers for enthusiasts typically range from approximately $3,500 to $20,000. Industrial printers may start around $10,000 and can cost more than $400,000.

Hobbyist mills and lathes start at $2,000, and an entry-level CNC machining center can begin at $60,000. Industrial 5-axis machining centers typically cost $500,000 or more.

Applications of Additive vs. Subtractive Manufacturing

Additive and subtractive manufacturing are used to produce a wide range of products across many industries. Additive manufacturing is often preferred for rapid prototyping, small-batch production, and on-demand production. Subtractive manufacturing has long been used to produce prototypes, but it is generally best suited for large production runs.

Additive manufacturing is used across nearly every industry, including aerospace, architecture, automotive, aviation, consumer goods, lifestyle, industrial

Pros and Cons Analysis

Pros of Subtractive Manufacturing

- Material Versatility: Subtractive manufacturing allows manufacturers to choose from an extensive variety of material sources, including various metals, polymers, wood, and advanced composites.

- Precision and Accuracy: The extreme precision and high accuracy of CNC machines enable the creation of complicated geometries while maintaining exceptionally tight tolerances.

- Superior Surface Finish: By producing high-quality surface finishes directly out of the machine, subtractive manufacturing often eliminates the need for extensive post-processing.

- Scalability: Subtractive manufacturing techniques are frequently appropriate for both large-scale and small-scale production, making them highly qualified for mass production of parts.

Cons of Subtractive Manufacturing

- Design Restrictions: Highly complex geometries or difficult-to-machine interior features may be impossible to produce using standard subtractive manufacturing techniques.

- Material Waste: Because surplus material is systematically machined away, a substantial amount of material waste is generated. This can increase both the environmental impact and the overall cost of raw materials.

- Longer Lead Times: Compared to some additive manufacturing setups, subtractive processes may require significantly more time for initial setup, actual machining, and the acquisition of specific materials.

When to Use Subtractive and Additive Manufacturing?

The decision between additive and subtractive manufacturing is typically based on the specific materials required for the project, the desired level of design complexity, the total production volume, and the unique requirements of the endeavor. In many cases, the most effective course of action is to combine the two approaches, leveraging the distinct advantages of each to accomplish the final goal.

Subtractive manufacturing procedures remain a preferred choice for several compelling reasons. For instance, CNC machining is excellent at achieving tight tolerances and extreme precision. If your project specifically calls for exact measurements, very specific features, or tight tolerances, subtractive manufacturing is often the superior option. Furthermore, it can be used with a vast array of materials, such as composites, metals, polymers, and wood. If your project requires specific materials with well-established and certified properties, subtractive manufacturing offers a broader range of choices. Additionally, because subtractive manufacturing is highly efficient and can utilize numerous machines at once, it is frequently more suited for large-scale industrial production. Subtractive manufacturing may also prove to be more affordable if you need to produce numerous identical items. Finally, if your product requires a perfectly smooth surface finish or specialized surface treatments, subtractive processes such as milling or grinding can produce the needed results more effectively.

On the other hand, additive manufacturing excels at constructing incredibly complicated geometries and elaborate designs that would be difficult, if not impossible, to produce through subtractive methods. Additive printing provides unparalleled design freedom and flexibility if your project contains intricate structures or complex internal details. Moreover, through the use of additive manufacturing, strong yet lightweight structures with optimized interior geometry can be produced using significantly less raw material. This is particularly advantageous in sectors where weight reduction is crucial, such as the aerospace and automotive industries. Furthermore, fast iterations and rapid design modifications are made possible by additive manufacturing, which eliminates the need for costly and time-consuming tooling, making it the perfect method for rapid prototyping. Additive manufacturing can produce functional prototypes much more swiftly if you need to develop and test them in a short timeframe. In addition, low-volume production and on-demand manufacturing are excellent use cases for additive technology. Additive manufacturing can be a highly cost-effective solution if you need to make small numbers of customized items without investing in expensive tooling or maintaining a large inventory.

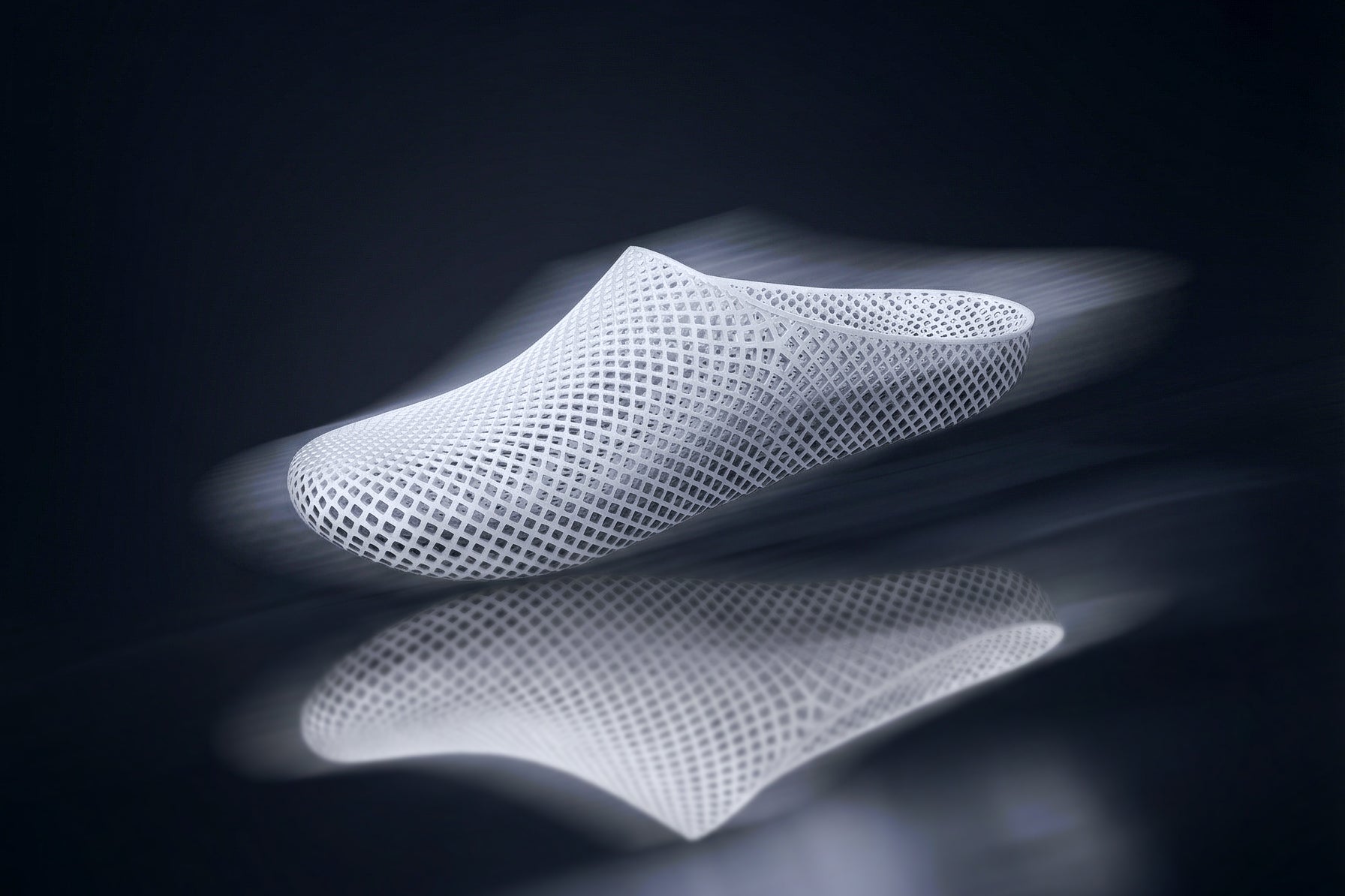

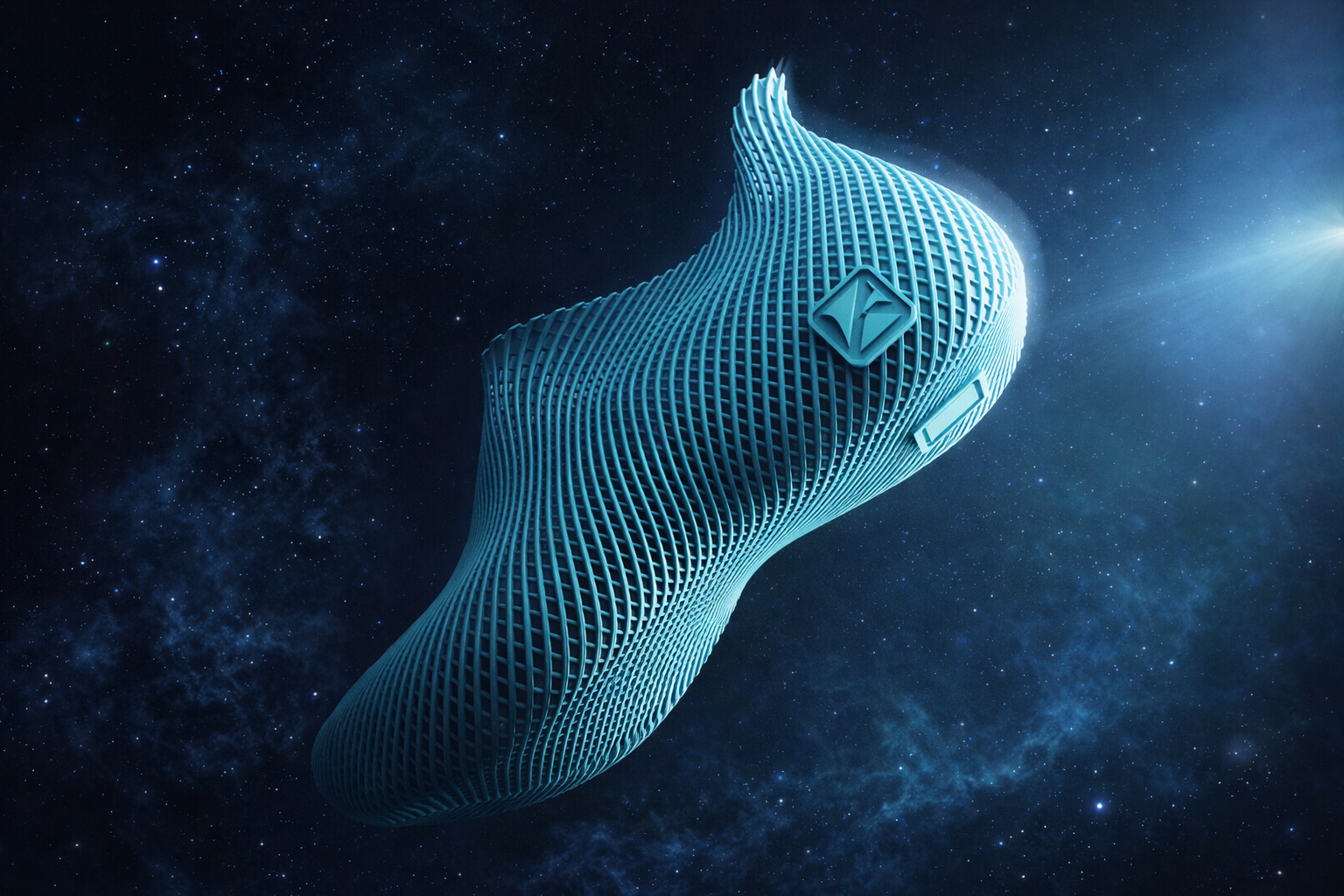

Do 3D-Printed Shoes Use Additive or Subtractive Manufacturing?

In the field of footwear manufacturing, 3D-printed shoes are generally produced using additive manufacturing techniques rather than subtractive methods. ARKKY 3D-printed shoes serve as a clear and prominent example of this approach, as they are manufactured using advanced AI-HALS additive printing technology. Instead of cutting, milling, or removing material from a solid block to form a shoe shape, ARKKY builds key footwear components—such as the high-performance midsole—layer by layer based on precise digital designs. This additive process enables the creation of complex lattice structures, allows for precise control over specific cushioning zones, and ensures efficient material usage. It also supports rapid design iterations and flexible small-batch production. As a result, ARKKY’s 3D-printed shoes effectively demonstrate how additive manufacturing delivers both exceptional performance and superior design flexibility in the context of modern footwear.

Hybrid Process: Implement Design to Prototype

Hybrid approaches successfully combine additive and subtractive processes, taking the best attributes of both worlds and incorporating them into a single, specialized machine. These hybrid systems capitalize on the unique strengths of both manufacturing methods but require specialized and often expensive equipment. Ultimately, hybrid manufacturing makes the production of highly complex parts both quicker and easier.

A practical example of this would be using subtractive methods to polish the surface of a 3D-printed part to a high shine, or using a CNC drill to create a hole within an additive part that requires a specifically tight tolerance.

Would you like me to translate this polished version into any other languages, or do you need help generating images for any of the specific technologies mentioned?

Share:

What is HALS 3D Printing? — Decoding the Mass Production Revolution in Original Resin Photopolymerization

History of 3D Printed Shoes: From Concept to Mainstream