Chapter 1: Introduction to HALS Printing Technology

HALS (Hindered Asynchronous Light Synthesis) belongs to the Vat Photopolymerization family. It is a 3D printing process designed for ultra-high-speed, industrial-grade mass production. Unlike traditional SLA (Stereolithography) and DLP (Digital Light Processing), HALS is not a simple "layer-by-layer curing and peeling" process. Instead, through innovations in physicochemical mechanisms, it enables a manufacturing method akin to "continuously pulling objects out of liquid."

1.1 Historical Background

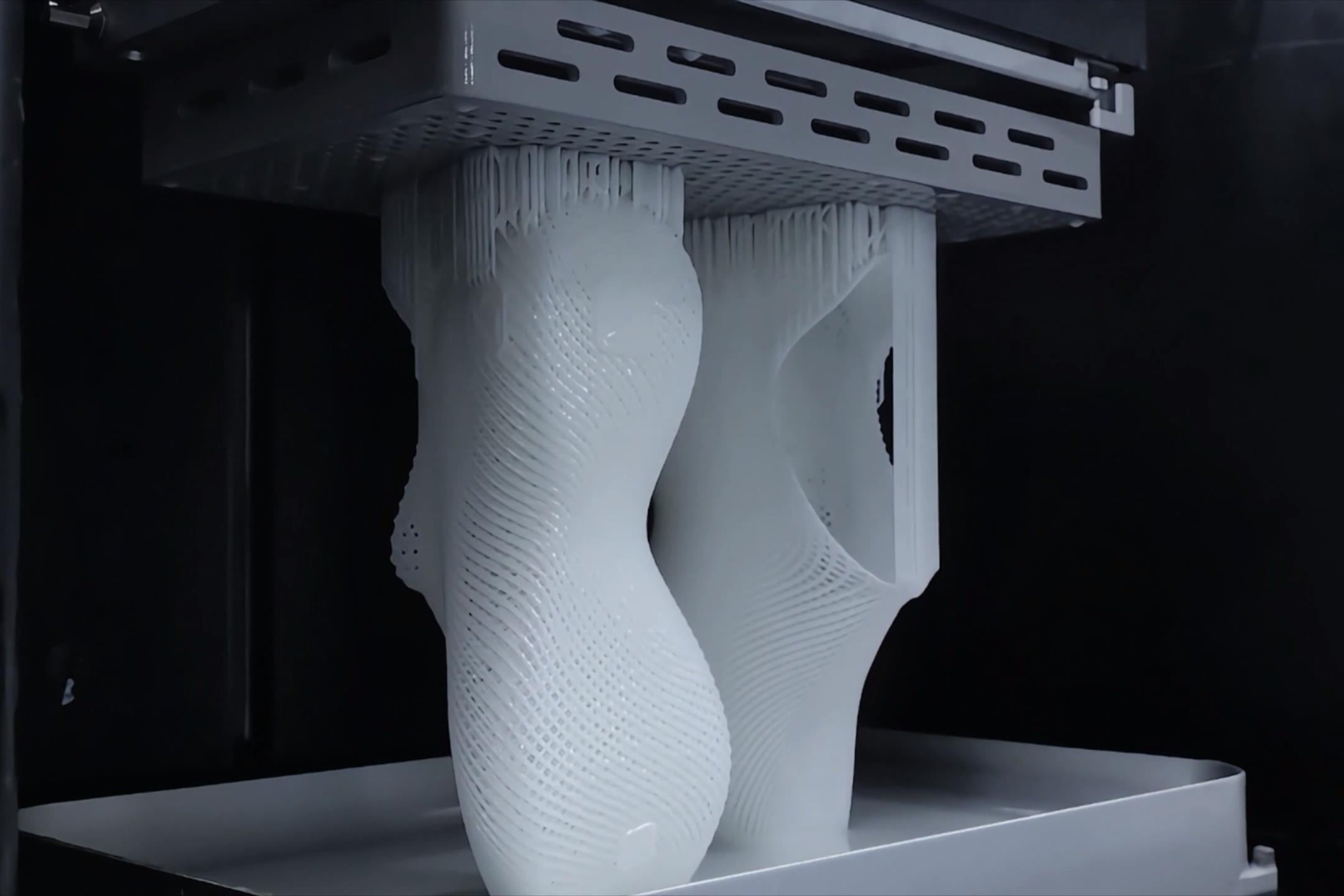

This technology was originally developed by PollyPolymer to address the bottlenecks in speed and material performance found in traditional 3D printing. Subsequently, it was adopted by brands like ARKKY for the large-scale production of consumer end-products, such as 3D-printed shoes. The emergence of HALS marks the transition of photopolymerization from "prototyping" to "End-use Part Production." ARKKY further introduced AI technology on top of HALS, referring to it as AIHALS.

1.2 Core Definition

The essence of HALS lies in utilizing AI algorithms and specialized chemical interface control to achieve a synergy between the "hindrance" of the photopolymerization reaction and the "asynchronous" nature of mechanical movement. This results in printing speeds 20 to 100 times faster than traditional SLA while imparting isotropic mechanical properties to the printed parts.

Chapter 2: The Physics of HALS

To understand HALS, one must delve into the two keywords in its name: "Hindered" and "Asynchronous."

2.1 The "Hindered" Mechanism: The Art of the Dead Zone

In traditional DLP/SLA printing, the resin adheres to the release film at the bottom of the vat as it cures. The printer must mechanically peel each layer after curing (the peel process), which significantly limits printing speed and can lead to the fracture of delicate structures.

HALS technology introduces a specialized Inhibition Layer mechanism.

- Chemical Inhibition: By creating a micron-thick layer rich in oxygen or other inhibitors above the transparent window (commonly known as the Dead Zone), the chain reaction of polymerization is rapidly quenched by the chemical substances, even though the photoinitiators are activated. Consequently, the resin remains uncured in this region.

- Fluid Replenishment: Because the resin stays liquid in the dead zone, fresh resin can flow to the curing interface extremely quickly. This means the printed part never actually touches the bottom optical window; instead, it cures while suspended on a "liquid air cushion." This non-contact continuous molding entirely eliminates the mechanical peeling step.

2.2 "Asynchronous" Control: AI-Driven Dynamic Synergy

Traditional printing is synchronous: Exposure -> Stop -> Z-axis Lift -> Exposure. This is a discrete, halting process. HALS adopts Asynchronous Control logic:

- Continuous Flow: The Z-axis lift is continuous, eliminating the need to pause for resin reflow (reflow is extremely smooth thanks to the dead zone).

- Dynamic Light Field: The underlying projection light source (typically a high-power UV LED matrix) is not a static projection. Instead, an AI algorithm dynamically adjusts the light intensity and exposure time based on the real-time position of the Z-axis, the rheological properties of the resin, and the current curing cross-sectional area.

- AI Integration: AIHALS further incorporates neural networks to predict heat accumulation and fluid dynamics during the printing process. By compensating for light parameters in real-time, it ensures sharp edges and an absence of internal stress concentration even during ultra-high-speed lifting (e.g., >300mm/hr).

Chapter 3: The HALS Workflow

The transformation from a digital model to a physical entity is highly automated and standardized in the HALS process.

3.1 Pre-processing

- Digital Embryo: Designers create CAD models, which are particularly suitable for generating extremely complex Lattice Structures.

- Voxelized Slicing: The software converts the model into a continuous stream of cross-sectional images (Video Stream) rather than discrete pictures. An AI pre-processor analyzes the overhanging parts of the model, automatically generates support structures, and calculates the optimal light power for every millisecond.

3.2 Printing Process

- Vat Filling: High-performance photopolymers are injected into the HALS printer's vat.

- Continuous Lifting: The build platform descends to touch the inhibition layer and then begins a continuous ascent. The UV light source projects the cross-sections onto the resin through the oxygen-permeable/transparent window at the bottom, much like playing a movie.

- Exothermic Control: Due to the extremely rapid reaction, a significant amount of polymerization heat is generated. HALS equipment is typically equipped with an efficient active cooling system to prevent warping caused by resin overheating.

3.3 Post-processing

- Cleaning: Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) or specialized solvents are used to wash away uncured resin residue from the surface.

- Thermal/UV Curing: This is key to the explosive performance of HALS materials. Most HALS materials (especially elastomers) utilize a Dual-cure mechanism. The initial printing only establishes the shape (the Green Part); subsequent heat treatment triggers a second chemical reaction (such as the cross-linking of polyurethane chains), thereby imparting the final strength and elasticity to the material.

Chapter 4: Material Ecosystem

PollyPolymer has built a massive material library for HALS technology, containing over 5000 formulations covering the full spectrum from flexible to rigid.

|

Material Category |

Property Description |

Typical Applications |

|

HALS Elastomers |

Feature extremely high rebound rates, tear resistance, and fatigue resistance. Not just "rubber-like," their physicochemical structure is that of polyurethane rubber. |

Running shoe midsoles (ARKKY), shock absorbers, seals |

|

Bio-based Resins |

Contain up to 53% bio-based content derived from renewable resources. Non-toxic when burned, they enable partial biodegradation or closed-loop recycling. |

Eco-friendly consumer goods, fashion accessories, 3D-printed monolithic shoes |

|

Tough Engineering Resins |

Similar in performance to ABS or PP, with impact resistance. Suitable for snap-fits and not easily brittle. |

Drone shells, automotive interior parts |

|

High-Temp Resins |

Heat deflection temperature (HDT) can exceed 200°C, maintaining rigidity at high temperatures. |

Mold inserts, electronic runner components |

Chapter 5: Technical Comparison (SLA vs. DLP vs. CLIP vs. HALS)

To better understand the positioning of HALS, we can compare it horizontally with mainstream photopolymerization technologies.

|

Feature |

SLA (Stereolithography) |

DLP (Digital Light Processing) |

CLIP (Carbon DLS) |

HALS (PollyPolymer) |

|

Light Source |

UV Laser beam (Point scanning) |

Projector (Area exposure) |

UV LED + Oxygen-permeable membrane |

AI Dynamic Light Field + Inhibition Layer |

|

Printing Mechanism |

Layer-by-layer curing (Laser tracing) |

Layer-by-layer curing (Pixel projection) |

Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP) |

Continuous High-speed Lifting (AIHALS) |

|

Printing Speed |

Slow (10-20 mm/hr) |

Medium (20-40 mm/hr) |

Fast (100+ mm/hr) |

Ultra-fast (200-500+ mm/hr) |

|

Surface Quality |

Very high, smooth |

Average, pixelated texture |

High, no layer lines |

High, no layer lines (Layerless) |

|

Mechanical Properties |

Anisotropic (Weak Z-axis) |

Anisotropic |

Isotropic |

Isotropic, Industrial-grade strength |

|

Main Consumables |

Epoxy/Acrylic resins |

Acrylic resins |

Polyurethane/Epoxy |

Modified Polyurethane/Bio-based materials |

|

Typical Applications |

Fine prototypes, jewelry |

Dental models, figurines |

Shoe midsoles, connectors |

Full shoe mass production, large industrial parts |

Key Differentiators:

- vs SLA: HALS is several orders of magnitude faster and offers better material aging performance.

- vs CLIP: Both utilize the dead zone principle, but HALS emphasizes AI-driven asynchronous control and large-format molding capabilities (making it more suitable for printing entire shoes rather than just midsoles), supported by a more open and extensive material library.

Chapter 6: Case Studies and Design Guidelines

6.1 Killer Application: Footwear Mass Production

The ARKKY brand is the premier ambassador for HALS technology.

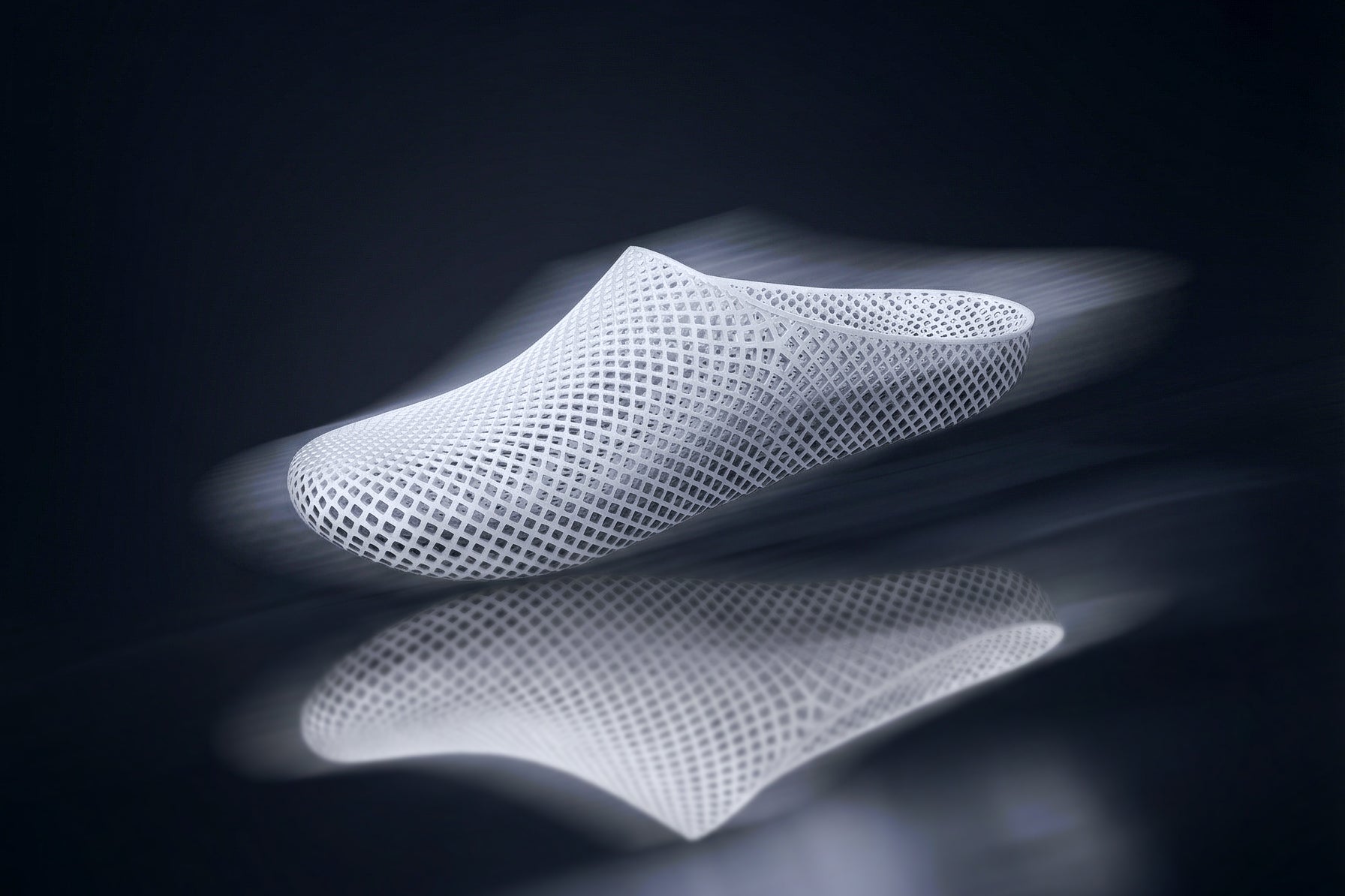

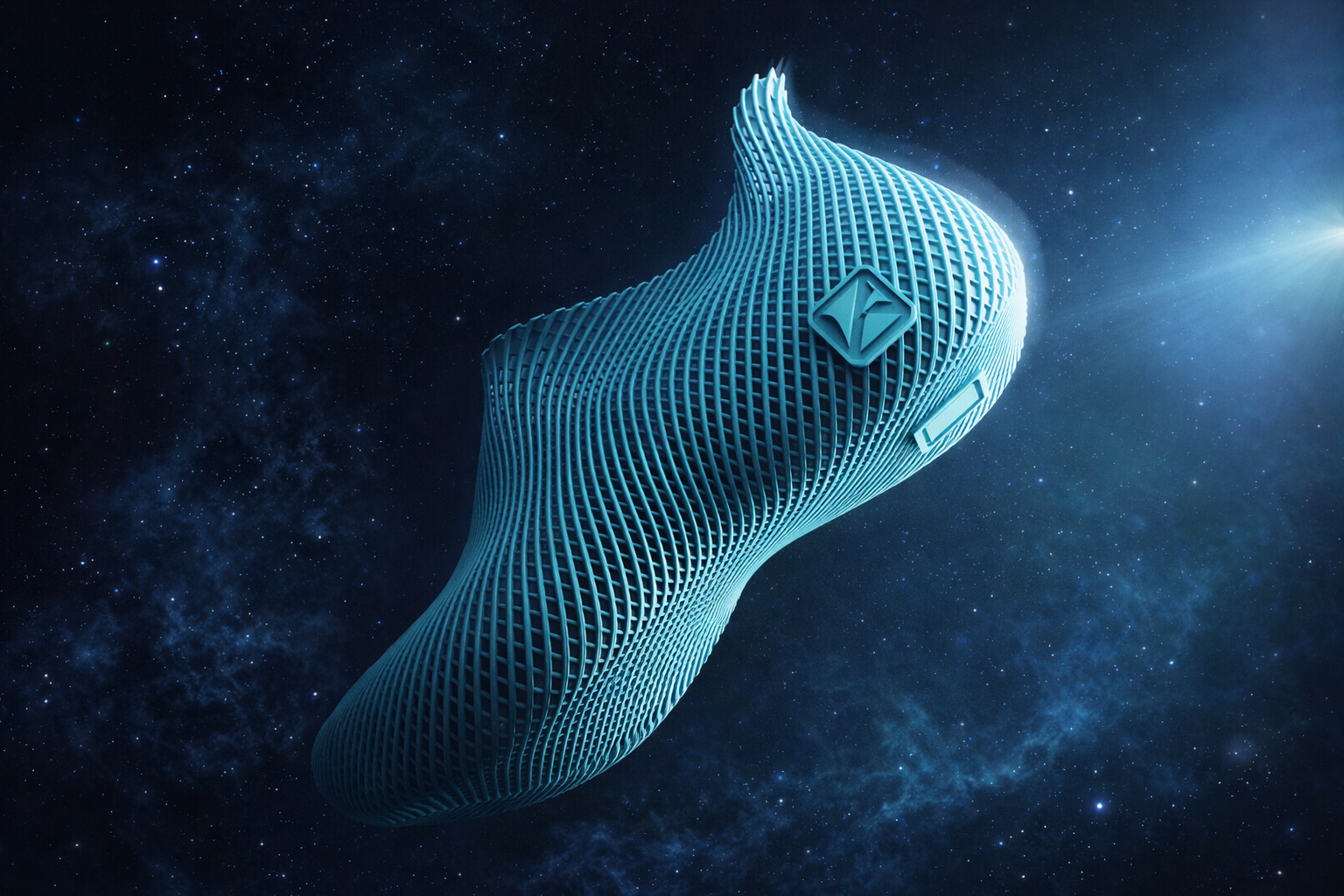

- Monolithic Molding: Leveraging the large-format molding capability of HALS, ARKKY can print an entire shoe, including the upper and the sole, in one go.

- Lattice Mechanics: Designs extensively utilize Lattice structures. HALS can perfectly reproduce even micro-lattices with wall thicknesses as thin as 0.2mm. These structures provide breathability and zonal cushioning performance that traditional foam materials cannot match.

- Supply Chain Revolution: Due to the extremely fast printing speed (approx. 20-60 minutes per shoe), factories can achieve "Zero Inventory" production, manufacturing in real-time based on orders.

6.2 Industry and Robotics

In the field of robotics, HALS is used to manufacture complex Soft Grippers and hydraulic components with internal flow channels. Their airtightness and pressure resistance reach injection-molding standards.

6.3 Design Guidelines

- Self-supporting Design: Utilize the 45° rule as much as possible to minimize support material.

- Drainage Holes: For hollow structures, at least two drainage holes with a diameter >3mm must be designed to prevent uncured resin from being trapped inside.

- Minimal Features: Recommended minimum wall thickness is 0.5mm, and minimum hole diameter is 0.8mm.

- Lattice Orientation: Consider the direction of force during printing when designing lattices; although HALS is isotropic, proper orientation can reduce fluid resistance during printing.

Conclusion

HALS printing technology is more than just an accelerated version of SLA; it is a ticket for additive manufacturing to enter Mass Production. Through AIHALS, PollyPolymer and ARKKY have proven that 3D printing can balance speed, quality, and cost, truly turning "Digital Manufacturing" into a "Digital Factory."

Share:

Additive vs. Subtractive Manufacturing: What’s the Difference?